Save Weeks of Analysis

Neighbour Spoofing in Voice Fraud: How Phone Scams Exploit Caller Trust

Neighbour spoofing is often dismissed as a minor scam technique.

That assumption is not just incomplete—it actively weakens voice fraud defenses.

“The most effective fraud techniques do not merely exploit individuals; they capitalize on systemic gaps in risk classification.”

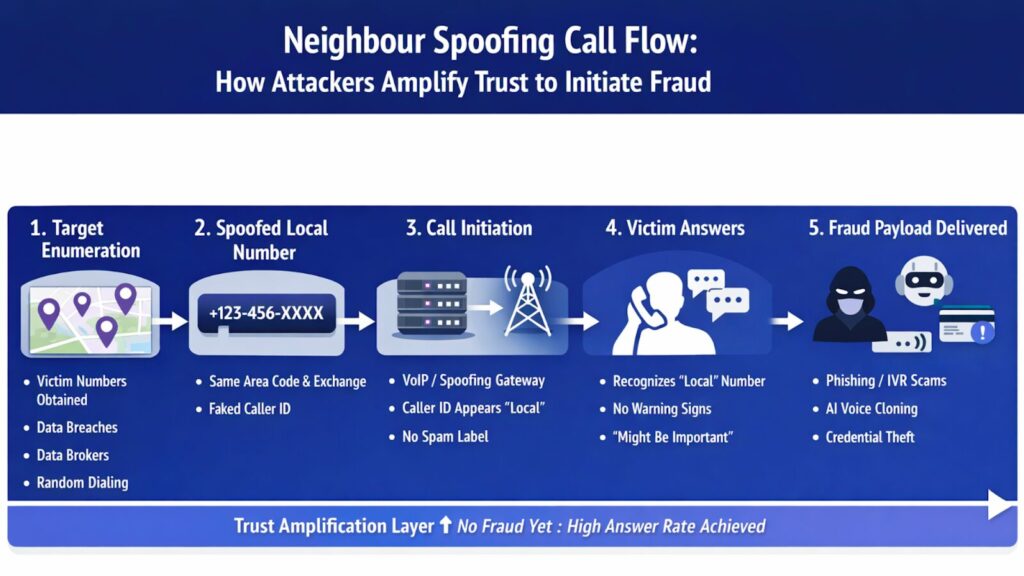

In today’s world of phone scams, neighbour spoofing isn’t the main attack. It’s a voice-fraud delivery technique in which attackers manipulate caller identity to appear geographically familiar, increasing call answer rates before any impersonation or fraud payload is introduced.

In today’s phone-based scams, this is used to lower suspicion, normalize the interaction, and increase engagement before more explicit social engineering occurs. Risk assessments often fail because calls are evaluated in isolation, rather than as part of a coordinated fraud pipeline.

At Infosprint, we analyze neighbour spoofing as part of the underlying infrastructure of fraud, not just background noise. This framing clarifies how it fits into fraud pipelines, why current safeguards miss it, and why overlooking phone risks leaves systems exposed.

Why Is Neighbour Spoofing Misclassified?

Most discussions place neighbour spoofing under “caller ID spoofing” and stop there. This collapses very different behaviors into a single bucket, obscuring the attacker’s intent.

Caller ID spoofing answers how a call appears.

Neighbour spoofing answers why a specific identity is chosen.

Attackers do not use local-looking numbers to impersonate a specific entity. They employ them to take advantage of heuristics related to regional familiarity that are ingrained in people’s evaluations of unfamiliar calls. The goal is to initiate engagement, not to persuade.

This distinction matters because neighbour spoofing is rarely the fraud event itself. It is the entry point that enables downstream techniques to function at scale.

Rather than being a threat in and of itself, neighbor spoofing should be viewed as a sublayer of larger phone spoofing techniques. Neighbor spoofing maximizes delivery and engagement prior to any overt impersonation, whereas phone spoofing concentrates on identity modification at the signal level.

Execution Logic: How Neighbour Spoofing Actually Works

a) Number Block Selection Is Deliberate, Not Random

Instead of replicating the victim’s number exactly, neighbor spoofing usually mimics the area code and exchange (NPA-NXX). This reduces the chances of detection and complaints, as a general locality still seems familiar to the recipient.

Attackers optimize for:

- Regional plausibility, not precision

- High density of callable numbers within a short radius

- Low reuse time per spoofed identity

This creates the appearance of “localness” without overexposing any single spoofed number to reputation systems.

The following video demonstrates how attackers leverage local number familiarity to increase pickup rates before any explicit fraud payload is introduced. Notice that the call’s effectiveness is driven not by impersonation or persuasion, but by geographic plausibility and timing—the same execution logic described above.

Real-world example of neighbour spoofing call behavior

b) Why Proximity Outperforms Brand Impersonation (Early in the Funnel)

Brand impersonation works after attention is secured. Neighbour spoofing works before attention exists.

A local-looking unknown number triggers different cognitive processing than a known brand:

- It suggests personal relevance (neighbour, delivery, service call)

- It avoids preloaded skepticism associated with banks, telecoms, or government names

- It benefits from ambiguity rather than authority

In early contact attempts, ambiguity consistently outperforms explicit identity claims. Neighbour spoofing leverages this by delaying contextual framing until the call is answered.

c) Rotation and Pattern Evasion

Neighbour spoofing only works if it stays ephemeral.

Attackers rotate spoofed numbers across:

- Adjacent exchanges

- Multiple carriers

- Short reuse windows

The rotation strategy focuses on how quickly answer rates decline instead of just looking at whether something is detected. Once the chances of successfully connecting drop, the number is simply abandoned, even if it hasn’t been flagged yet. This approach makes neighbor spoofing especially tough for reputation-based defenses that rely on building up over time.

System Constraints That Enable Neighbour Spoofing

Caller ID Was Never Designed as Authentication

Caller ID is a presentation layer, not a verification mechanism. Legacy telephony systems assume trust between interconnected networks and prioritize call completion over identity validation.

This architectural assumption persists across:

- Inter-carrier signaling

- Legacy PBX environments

- International routing paths

Neighbour spoofing exploits this gap without breaking or bypassing systems—it simply operates within their original trust model.

What STIR/SHAKEN Does Not Solve

Call authentication frameworks improve origin attestation, not intent validation.

A call can be:

- Cryptographically verified

- Properly signed

- Fully compliant

and still be malicious.

Additionally:

- Many call paths remain unsigned

- Cross-border calls often bypass enforcement

- Enterprise and legacy systems introduce trust discontinuities

Neighbour spoofing does not rely on impersonating a protected brand, so authentication alone cannot neutralize its effectiveness.

This gap between authentication and intent validation is why neighbour spoofing continues to succeed. Managing voice-channel risk requires treating telephony as an adversarial surface—one that must be evaluated alongside identity, network behavior, and fraud signals, rather than as a trusted utility layer.

Why Spam Labels Lag Behind Attacker Behavior

Spam labeling systems are reactive by design. They require:

- Sufficient call volume

- User complaints

- Pattern stability

Neighbour spoofing undermines all three:

- Low dwell time per number

- Distributed volume across blocks

- Rapid identity churn

By the time a label appears, the attacker has already moved on.

Where Neighbour Spoofing Fits in the Voice Fraud Stack

Early-Stage Engagement Layer

Neighbour spoofing sits at the top of the fraud funnel. Its sole function is to maximize call answer rates while minimizing initial suspicion.

It precedes:

- Scripted social engineering

- IVR replay systems

- AI-generated voice payloads

- Brand or authority impersonation

Think of it as delivery infrastructure, not content.

Relationship to Other Voice Fraud Techniques

- Bank spoofing: Higher trust, higher scrutiny, later-stage deployment

- IVR replay: Automation layer after engagement

- AI voice synthesis: Payload sophistication, not delivery optimization

Neighbour spoofing is chosen early because it is:

- Low cost

- Low attribution risk

- Highly adaptable

Once engagement is achieved, attackers can escalate to more explicit and detectable techniques.

Why Common Voice Fraud Defenses Fail

a) Blocklists Cannot Win

Blocklists assume finite identities. Neighbour spoofing operates in an effectively infinite number space with disposable caller identities.

Blocking individual numbers addresses symptoms, not behavior.

Neighbour spoofing does not rely on long-lived caller identities. Numbers are selected, used, and discarded based on pickup-rate performance, not exposure.

From the attacker’s perspective:

- A number is not an asset

- It is a temporary delivery handle

- Its lifespan is measured in minutes or hours

Once answer rates decline, the number is rotated—often before it accumulates enough negative reputation to trigger blocking.

b) User Education Does Not Scale

Education assumes attention, recall, and deliberate judgment. Voice interactions systematically undermine all three.

Voice calls are interruptive by design. They occur:

- During unrelated tasks

- Under time pressure

- Without prior context

Unlike email, a voice call demands an immediate response. There is no buffer for analysis, preview, or delayed engagement. Even trained users are forced to make real-time decisions before they can apply learned caution.

Voice-based attacks exploit reflexive behavior, time pressure, and habituation. Even well-trained users will answer local-looking calls under the right conditions.

c) Organizations Underestimate Voice-Channel Risk

Most enterprises do not consciously ignore voice risk. They underestimate it owing to structural, historical, and organizational factors shaping how risk is perceived and prioritized.

Voice Is Categorized as Infrastructure, Not an Attack Surface

Voice systems are typically grouped with:

- Telephony infrastructure

- Network uptime

- Cost optimization and vendor management

This framing pushes voice into operations rather than security architecture. As a result, voice channels are rarely modeled using the same threat assumptions applied to email, identity, or endpoints. Security teams protect assets they can see and instruments. Voice offers are not offered by default.

Reframing the Threat Model

Neighbour spoofing does not steal credentials.

It does not execute fraud.

It enables everything that follows.

Treating it as a nuisance tactic leads to ineffective controls. Treating it as a trust-amplification layer requires a different defensive posture—one focused on behavioral analysis, call-flow intelligence, and upstream risk modeling.

As long as voice channels are evaluated only at the point of payload delivery, neighbour spoofing will remain an efficient and reliable entry mechanism for fraud operations.Organizations reassessing how voice fits into their broader fraud and security models can discuss voice fraud security exposure within the context of their existing risk architecture

Frequently Asked Questions

Caller ID spoofing explains how a number is presented. Neighbour spoofing explains why a local-looking identity is chosen—to exploit geographic familiarity and increase answer rates before any fraud payload is delivered.

STIR/SHAKEN validates call origin, not intent. A call can be authenticated yet still malicious. Neighbour spoofing exploits this gap by optimizing delivery and engagement rather than impersonating protected identities.

Detection requires behavioral and call-flow analysis, such as rotation velocity, exchange-level abuse, and engagement patterns. Number-based reputation and identity checks typically activate too late.

Signals include rapid caller ID rotation, localized exchange targeting, short reuse windows, and abnormal pickup-rate optimization—patterns that appear before explicit impersonation or payload delivery.

Blocklists assume stable identities, while neighbour spoofing uses disposable numbers. Education assumes attention and deliberation, but voice calls force real-time decisions under interruption and ambiguity.

Voice is treated as infrastructure, not an attack surface. Limited telemetry, fragmented ownership, and lack of behavioral visibility cause early-stage delivery risks like neighbour spoofing to go unmodeled.

Related Blogs

AI Health Kiosks: A Security and Compliance Perspective

Beyond ISO 27001: DPDP Compliance Gaps Your Audits Are Missing